1. Discovering BDD

The script for this chapter is currently in Google Docs

2. Example Mapping

In his seminal book, The Mythical Man-Month, Fred Brooks said:

"The hardest single part of building a software system is deciding precisely what to build."

The Mythical Man-Month

This is where the BDD practice of Discovery comes in.

We’re going to learn about a technique for doing discovery called Example Mapping: a way to structure the conversation between the Three Amigos - Tester, Developer and Product Owner - that explores the work to be done in order to build a detailed, shared understanding of the scope of the work, before you write any code.

2.1. Example Mapping: Why?

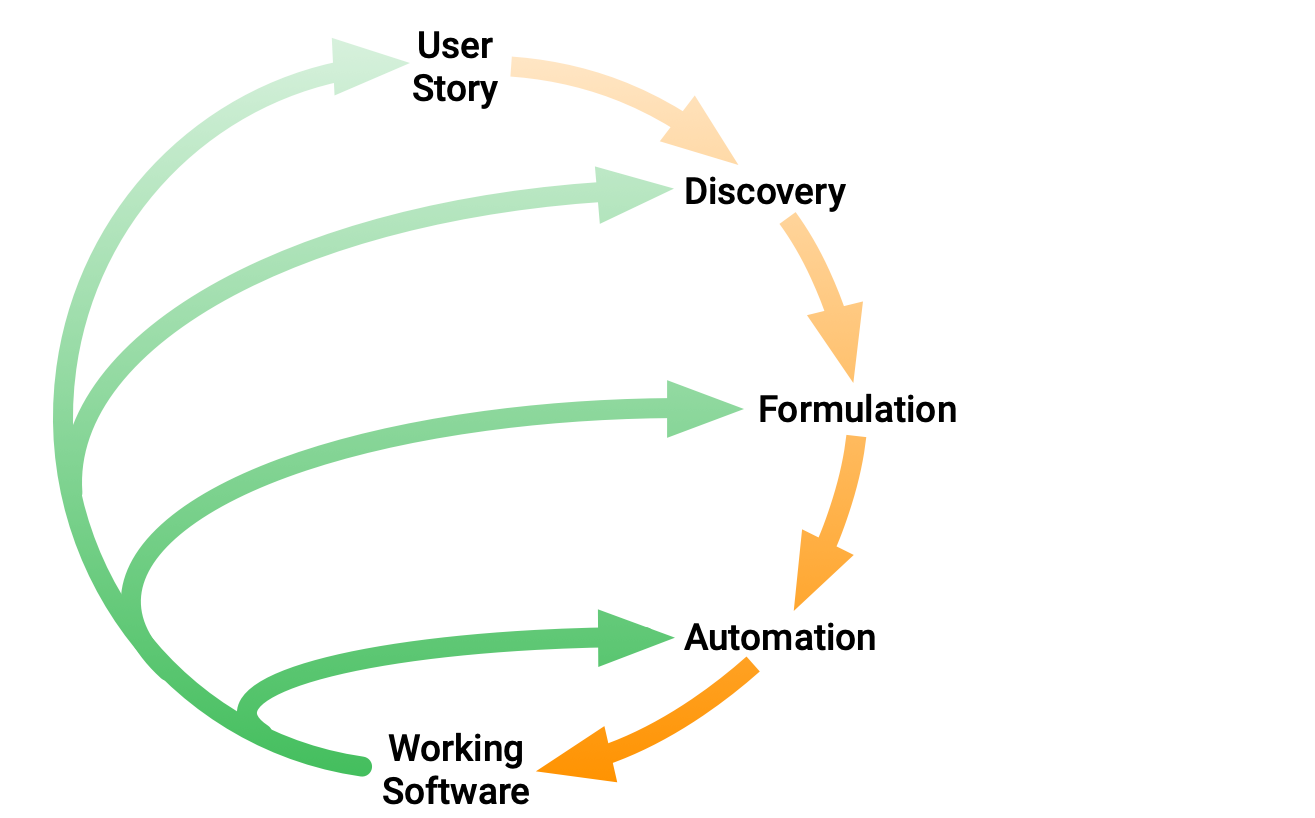

The three practices we introduced in Chapter 1 - Discovery, Formulation and Automation - are meant to be done in a sequence, in a series of rapid iterations.

Many teams are not used to working this way, because they think that testing (where a lot of the discovery happens) is something you do at the end.

This is what the famous management consultant, W. Edwards Demming, ridiculed as:

Let’s make toast: you burn it, I’ll scrape it.

Teams like this usually jump straight into Automation - writing the implementation of the feature. If they’re using Cucumber, they do a bit of Formulation - just enough to automate a test for the feature, but without really thinking very hard about what all the different scenarios are. They probably add these tests after they’ve done the implementation, or perhaps in parallel. They certainly don’t use them to drive the development of the implementation.

Finally, much of the Discovery happens at the end once someone has a chance to test the feature by hand, and really starts to think about the edge-cases.

Viewed from a BDD practitioner’s eyes, they’re doing everything backwards.

In software projects, it’s often the unknown unknowns that can make the biggest difference between success and failure. In BDD, we always try to assume we’re ignorant of some important information and try to deliberately discover those unknown unknowns as early as possible, so they don’t surprise us later on.

A team that invests just a little bit extra in Discovery, before they write any code, saves themselves a huge amount of wasted time further down the line.

In lesson 1, we showed you an example of the Three Amigos - Tester, Developer and Product owner - having a conversation about a new user story.

Nobody likes long meetings, so we’ve developed a simple framework for this conversation that keeps it quick and effective. We call this Example Mapping.

An Example Mapping session takes a single User Story as input, and aims to produce four outputs:

-

Business Rules, that must be satisified for the story to be implemented correctly

-

Examples of those business rules playing out in real-world scenarios

-

Questions or Assumptions that the group of people in the conversation need to deal with soon, but cannot resolve during the immediate conversation

-

New User Stories sliced out from the one being discussed in order to simplify it.

We capture these, as we talk, using index cards, or another virtual equivalent.

Working with these simple artefacts rather than trying to go straight to formulating Gherkin, allows us to keep the conversation at the right level - seeing the whole picture of the user story without getting lost in details.

2.1.1. Lesson 1 - Questions

Why did we say the development team’s initial attempt at the premium accounts feature was "done backwards"?

-

They did Discovery before Automation

-

They did Discovery before Formulation

-

They started with Automation, without doing enough Discovery or Formulation first (Correct)

-

They started with Discovery, then did Formulation and finally Automation

Explanation:

The intended order is Discovery, Formulation then Automation. Each of these steps teaches us a little more about the problem.

Our observation was that the the team jumped straight into coding (Automation), retro-fitting a scenario later. The discovery only happened when Tamsin tested the feature.

What does "Deliberate Discovery" mean (Multiple choice)

-

One person is responsible for gathering the requirements

-

Discovery is something you can only do in collaboration with others

-

Having the humility to assume there are things you don’t yet understand about the problem you’re working on (Correct)

-

Embracing your ignorance about what you’re building (Correct)

-

There are no unknown unknowns on your project

Explanation:

Deliverate Discovery means we assume that there are important things we don’t yet know about the project we’re working on, and so make a deliberate effort to look for them at every opportunity.

Although we very much encouage doing that collaboratively, it’s not the main emphasis here.

Read Daniel Terhorst-North’s original blog post.

Why is it a good idea to try and slice a user story?

-

Working in smaller pieces allows us to iterate and get feedback faster (Correct)

-

We can defer behaviour that’s lower priority (Correct)

-

Smaller stories are less likely to contain unknown unknowns (Correct)

-

Doing TDD and refactoring becomes much easier when we proceed in small steps (Correct)

-

Small steps help us keep momentum, which is motivating (Correct)

Explanation:

Just like grains of sand flow through the neck of a bottle faster than pebbles, the smaller you can slice your stories, the faster they will flow through your development team.

It’s important to preserve stories as a vertical slice right through your application, that changes the behaviour of the system from the point of view of a user, even in a very simple way.

That’s why we call it slicing rather than splitting.

Why did we discourage doing Formulation as part of an Example Mapping conversation?

-

Trying to write Gherkin slows the conversation down, which means you might miss the bigger picture. (Correct)

-

It’s usually an unneccesary level of detail to go into when you’re trying to discover unknown unknowns. (Correct)

-

Formulation should be done by a separate team

-

One person should be in charge of the documentation

Explanation

This is why we’ve separated Discovery from Formulation. It’s better to stay relatively shallow and go for breadth at this stage - making sure you’ve looked over the entire user story without getting pulled into rabbit holes.

Product Owners and Domain Experts are often busy people who only have limited time with the team. Make the most of this time by keeping the conversation at the level where the team can learn the maximum amount from them.

2.2. Example Mapping: How?

We first developed example mapping in face-to-face meeting using a simple a multi-colour pack of index cards and some pens. For teams that are working remotely, there are many virtual equivalents of that nowadays.

We use the four different coloured cards to represent the four main kinds of information that arise in the conversation.

We can start with the easy stuff: Take a yellow card and write down the name of the story.

Now, do we already know any rules or acceptance criteria about this story?

Write each rule down on a blue card:

They look pretty straightforward, but let’s explore them a bit by coming up with some examples.

Darren the developer comes up with a simple scenario to check he understands the basics of the “buy” rule: "I start with 10 credits, I shout buy my muffins and then I want to buy some socks, then I have zero credits. Correct?"

"Yes", says Paula.

Darren writes this example up on a green card, and places it underneath the rule that it illustrates.

Tammy the tester chimes in: "How about the one where you shout a word that contains buy, like buyer for example? If you were to shout I need a buyer for my house. Would that lose credits too?"

Paula thinks about it for a minute, and decides that no, only the whole word buy counts. They’ve discovered a new rule! They write that up on the rule card, and place the example card underneath it.

Darren asks: "How do the users get these credits? Are we building that functionality as part of this story too?"

Paula tells him that’s part of another story, and they can assume the user can already purchase credits. They write that down as a rule too.

This isn’t a behaviour rule - it’s a rule about the scope of the story. It’s still useful to write it down since we’ve agreed on it. But it won’t need any examples. We could also have chosen to use a red card her to write down our assumption.

Still focussed on the “buy” rule, Tammy asks: "What if they run out of credit? Say you start with 10 credits and shout buy three times. What’s the outcome?"

Paula looks puzzled. "I don’t know". She says. I’ll need to give that some thought.

Darren takes a red card and writes this up as a question.

They apply the same technique to the other rule about long messages, and pretty soon the table is covered in cards, reflecting the rules, examples and questions that have come up in their conversation. Now they have a picture in front of them that reflects back what they know, and still don’t know, about this story.

2.2.1. Lesson 2 - Questions

What do the Green cards represent in an example map?

-

Stories

-

Rules

-

Examples (Correct)

-

Questions or assumptions

Explanation:

We use the green card to represent examples because when we turn them into tests we want them to go green and pass!

What do the Blue cards represent in an example map?

-

Stories

-

Rules (Correct)

-

Examples

-

Questions or assumptions

Explanation:

We use the blue cards to represent rules because they’re fixed, or frozen, like blue ice.

What do the Red cards represent in an example map?

-

Stories

-

Rules

-

Examples

-

Questions or assumptions (Correct)

Explanation:

We use the red cards to represent questions and assumptions because it indicates danger! There’s still some uncertainty to be resolved here.

What do the Yellow cards represent in an example map?

-

Story (Correct)

-

Rule

-

Example

-

Question or assumption

Explanation:

We chose the yellow cards to represent stories in our example mapping sessions, mostly because that was the last colour left over in the pack!

Look at the following example map. Do you think the team is ready to start coding yet?

-

No. There are still a lot of questions to resolve.

-

No. They probably haven’t explored the story enough yet. More conversation needed. (Correct)

-

No. There are too many rules. They should try to slice the story first.

-

Yes. There’s a good number of examples for each rule, and no questions.

Explanation:

When an example map shows only a few cards, and some rules with no examples at all, it suggests that either the story is very simple, or the discussion hasn’t gone deep enough yet.

Look at the following example map. Do you think the team is ready to start coding yet?

-

No. There are still a lot of questions to resolve.

-

No. They probably haven’t explored the story enough yet. More conversation needed.

-

No. There are too many rules. They should try to slice the story first.

-

Yes. There’s a good number of examples for each rule, and no questions. (Correct)

Explanation:

This example map shows a good number of examples for each rule, and no questions. If the team feel like the conversation is finished, then they’re probably ready to start hacking on this story.

Look at the following example map. Do you think the team is ready to start coding yet?

-

No. There are still a lot of questions to resolve. (Correct)

-

No. They probably haven’t explored the story enough yet. More conversation needed.

-

No. There are too many rules. They should try to slice the story first.

-

Yes. There’s a good number of examples for each rule, and no questions.

Explanation:

The large number of red cards here suggests that the team have encountered a number of questions that they couldn’t resolve themselves. Often this is an indication that there’s someone missing from the conversation. It would probably be irresponsible to start coding until at least some of those questions have been resolved.

Look at the following example map. Do you think the team is ready to start coding yet?

-

No. There are still a lot of questions to resolve.

-

No. They probably haven’t explored the story enough yet. More conversation needed.

-

No. There are too many rules. They should try to slice the story first. (Correct)

-

Yes. There’s a good number of examples for each rule, and no questions.

Explanation:

When an example map is wide like this, with a lot of different rules, it’s often a signal that there’s an opportunity to slice the story up by de-scoping some of those rules from the first iteration. Even if it’s not something that would be high enough quality to ship to a customer, you can often defer some of the rules into another story that you can implement later.

2.3. Example Mapping: Conclusions

As you’ve just seen, an example mapping session should go right across the breadth of the story, trying to get a complete picture of the behaviour. Inviting all three amigos - product owner, tester and developer - is important because each perspective adds something to the conversation.

Although the apparent purpose of an example mapping session is to take a user story, and try to produce rules and examples that illustrate the behaviour, the underlying goal is to achieve a shared understanding and agreement about the precise scope of a user story. Some people tell us that example mapping has helped to build empathy within their team!

With this goal in mind, make sure the session isn’t just a rubber-stamping exercise, where one person does all the talking. Notice how in our example, everyone in the group was asking questions and writing new cards.

In the conversation, we often end up refining, or even slicing out new user stories to make the current one smaller. Deciding what a story is not - and maximising the amount of work not done - is one of the most useful things you can do in a three amigos session. Small stories are the secret of a successful agile team.

Each time you come up with an example, try to understand what the underlying rule or rules are. If you discover an example that doesn’t fit your rules, you’ll need to reconsider your rules. In this way, the scope of the story is refined by the group.

Although there’s no doubt of the power of examples for exploring and talking through requirements, it’s the rules that will go into the code. If you understand the rules, you’ll be able to build an elegant solution.

As Dr David West says in his excellent book "Object Thinking", If you problem the solution well enough, the solution will take care of itself.

Sometimes, you’ll come across questions that nobody can answer. Instead of getting stuck trying to come up with an answer, just write down the question.

Congratulations! You’ve just turned an unknown unknown into a known unknown. That’s progress.

Many people think they need to produce formal Gherkin scenarios from their three amigos conversations, but in our experience that’s only occasionally necessary. In fact, it can often slow the discussion down.

The point of an example mapping session is to do the discovery work. You can do formulation as a separate activity, next.

One last tip is to run your example mapping sessions in a timebox. When you’re practiced at it, you should be able to analyse a story within 25 minutes. If you can’t, it’s either too big, or you don’t understand it well enough yet. Either way, it’s not ready to play.

At the end of the 25 minutes, you can check whether everyone thinks the story is ready to start work on. If lots of questions remain, it would be risky to start work, but people might be comfortable taking on a story with only a few minor questions to clear up. Check this with a quick thumb-vote.

2.3.1. Lesson 3 - Questions

Which of the following are direct outcomes you could expect if your team starts practcing Example Mapping?

-

Less rework due to bugs found in your stories (Correct)

-

Greater empathy and mutual respect between team members (Correct)

-

Amazing Gherkin that reads really well

-

Smaller user stories (Correct)

-

A shared understanding of what you’re going to build for the story (Correct)

-

More predicatable delivery pace (Correct)

-

A quick sense of whether a story is about the right size and ready to start writing code. (Correct)

Explanation:

We don’t write Gherkin during an example mapping session, so that’s not one of the direct outcomes, though a good example mapping session should leave the team ready to write their best Gherkin.

Which of the following presents the most risk to your project?

-

Unknown unknowns (Correct)

-

Known unknowns

-

Known knowns

Explanation:

In project management, there are famously "uknown unknowns", "known unknowns" and "known knowns". The most dangerous are the "unknown unknows" because not only do we not know the answer to them, we have not even realised yet that there’s a question!